Why Soil Nutrient Cycles Matter More Than You Think

Healthy soil is the foundation of every thriving garden and farm. Understanding the soil nutrient cycle is like learning the secret language of your plants—it tells you how nutrients move, transform, and support growth. Without this balance, plants struggle to absorb the essential elements they need to flourish. A well-managed nutrient cycle not only enhances crop yield but also maintains the long-term fertility of your soil.

This guide will help you achieve a better understanding of your soil’s nutrient cycle, from its natural processes to the best practices for maintaining a balanced, sustainable ecosystem beneath your feet.

What Is the Soil Nutrient Cycle?

Definition and Core Concepts

The soil nutrient cycle refers to the natural movement and transformation of essential nutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) through the soil, plants, and environment. It’s a dynamic, self-sustaining system where nutrients are continuously recycled and reused. When this cycle functions efficiently, your soil remains fertile, and your plants grow stronger and healthier.

The Role of Soil Organisms in Nutrient Cycling

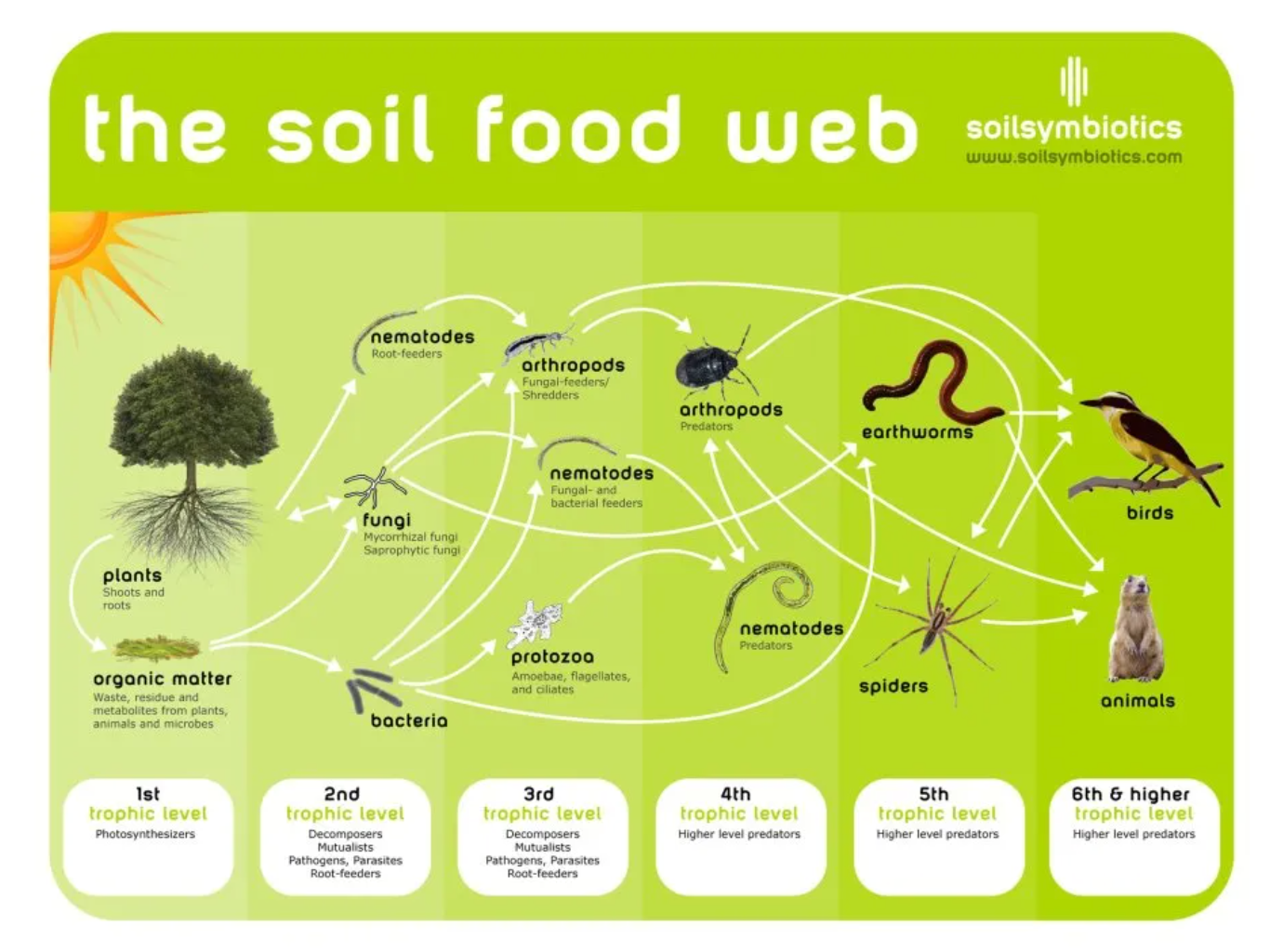

Soil microorganisms—such as bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and earthworms—are the unseen heroes of this process. They break down organic matter, convert nutrients into plant-available forms, and improve soil structure. For example, nitrogen-fixing bacteria transform atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use, while decomposers release minerals from decaying plant and animal material.

Major Nutrients in Soil and Their Functions

Macronutrients: Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium

These are the primary nutrients plants require in large amounts. Nitrogen promotes leafy growth, phosphorus supports root development and flowering, and potassium enhances disease resistance and water regulation.

Micronutrients: Iron, Zinc, Manganese, and Others

Even though they’re needed in smaller amounts, micronutrients are crucial for enzyme activity, photosynthesis, and overall plant vitality. Deficiencies can cause yellowing leaves, stunted growth, or reduced yields.

The Interplay Between Organic Matter and Nutrient Availability

Organic matter acts as a nutrient bank. As it decomposes, it releases essential minerals and improves the soil’s ability to retain moisture and nutrients. Regularly adding compost or mulch ensures that your soil remains rich and balanced.

The Four Stages of the Soil Nutrient Cycle

1. Mineralization: Unlocking Nutrients from Organic Matter

In this stage, microorganisms break down organic residues (like dead roots and leaves) into inorganic nutrients that plants can absorb. It’s the process that makes compost so valuable in gardens.

2. Immobilization: Temporary Nutrient Storage by Microbes

Here, microbes “borrow” nutrients for their own growth. Although this temporarily reduces the nutrients available to plants, it’s essential for long-term soil health, as these nutrients are later released back into the cycle.

3. Nitrification: Transforming Ammonium into Nitrate

Ammonium (NH₄⁺) is converted into nitrate (NO₃⁻) by specialized bacteria. Plants readily absorb nitrate, making this phase vital for nitrogen availability.

4. Denitrification: Nutrient Loss Back to the Atmosphere

In waterlogged or compacted soils, nitrate can be converted back to nitrogen gas and lost to the atmosphere. Managing soil moisture and aeration minimizes this loss.

Factors Affecting the Soil Nutrient Cycle

Soil Texture and Structure

Sandy soils drain too quickly, leading to nutrient leaching, while clay soils may retain too much water, causing root stress. Loamy soils strike the perfect balance for nutrient retention and plant uptake.

Temperature, Moisture, and Aeration

Biological activity peaks when soils are warm and moist but well-aerated. Extreme dryness or saturation slows microbial processes, disrupting the nutrient cycle.

Human Activities and Soil Management Practices

Overuse of chemical fertilizers, tilling, and poor crop rotation can degrade soil health. Sustainable practices—like organic fertilization and minimal tillage—help maintain nutrient balance naturally.

The Role of Organic Matter in Sustaining the Cycle

Composting and Decomposition Processes

Organic matter is the lifeblood of a healthy soil ecosystem. Through decomposition, it provides a steady supply of nutrients that plants can absorb over time. Composting mimics nature’s recycling system—organic materials such as food scraps, grass clippings, and leaves are broken down by microorganisms into humus, a dark, nutrient-rich substance that enhances soil structure and fertility.

This decomposition process also releases carbon dioxide, which fuels photosynthesis in plants. Additionally, humus improves the soil’s ability to retain water and nutrients, reducing the need for frequent fertilization. Regularly adding compost helps maintain a consistent nutrient flow, creating an ideal environment for beneficial soil life.

How Cover Crops Improve Nutrient Cycling

Cover crops like clover, rye, and vetch play a crucial role in maintaining soil fertility between growing seasons. They prevent erosion, suppress weeds, and add organic matter when tilled back into the soil. Leguminous cover crops, in particular, fix atmospheric nitrogen and enrich the soil naturally. When incorporated into the soil, these plants decompose, releasing essential nutrients that keep the nutrient cycle active even during off-seasons.

Enhancing Soil Fertility Naturally

Using Compost, Manure, and Green Waste Effectively

Organic amendments are the cornerstone of sustainable nutrient management. Compost adds a balanced mix of nutrients, while well-aged manure provides an immediate boost of nitrogen and phosphorus. Green waste like chopped weeds or crop residues can be turned into the soil to feed microbes and stimulate biological activity.

It’s important to apply these materials correctly—too much fresh manure can burn roots, while poorly decomposed organic matter can temporarily lock up nitrogen. Always allow organic materials to mature fully before adding them to your garden beds.

Crop Rotation and Intercropping for Balanced Nutrient Use

Crop rotation is a time-tested technique that prevents nutrient depletion. By alternating deep-rooted and shallow-rooted plants—or legumes and non-legumes—you allow the soil to recover and replenish. Intercropping, the practice of growing complementary crops together (like beans and corn), optimizes nutrient use and supports diverse soil organisms.

For instance, beans fix nitrogen that corn later utilizes, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. These traditional methods maintain the nutrient cycle and promote long-term soil health.

Mycorrhizal Fungi and Their Benefits

These beneficial fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, extending their reach into the soil. Mycorrhizae improve the uptake of phosphorus, zinc, and water, while also protecting plants from stress and disease. Incorporating mycorrhizal inoculants into your soil can significantly boost your plants’ nutrient absorption efficiency, completing the natural nutrient loop.

Common Problems in Nutrient Cycling and How to Fix Them

Nutrient Leaching and Runoff

Excess rainfall or irrigation can wash nutrients away before plants can absorb them. This not only wastes fertilizers but also pollutes nearby waterways. To prevent leaching, add organic matter to improve soil structure, use mulch to slow water flow, and plant deep-rooted crops to capture lost nutrients.

Soil Compaction and Poor Drainage

When soil becomes compacted, air and water can’t move freely, suffocating roots and microbes. To fix compaction, avoid walking on wet soil, use raised beds, and occasionally aerate the soil. Adding compost also helps loosen compacted layers naturally.

Acidification and pH Imbalance

Soil pH affects how available nutrients are to plants. Acidic soils (low pH) can lock up essential minerals like phosphorus, while alkaline soils (high pH) can restrict iron and manganese. Regular soil testing and balanced amendments—like lime for acidity or sulfur for alkalinity—help restore optimal pH levels.

Testing and Monitoring Soil Health

How to Conduct a Soil Test

A soil test is the best way to understand your soil’s nutrient status. Collect samples from different parts of your garden or field, mix them together, and send them to a local agricultural lab. They’ll analyze pH, organic matter, and nutrient content, providing recommendations for balanced fertilization.

Interpreting Soil Test Results Correctly

Soil test reports can be intimidating, but they’re incredibly valuable. Look for macronutrient (N-P-K) levels, micronutrient availability, and organic matter percentages. Use these results to adjust your nutrient inputs precisely—ensuring plants get what they need without overloading the soil.

Sustainable Soil Management Practices for Gardeners and Farmers

Integrated Nutrient Management (INM)

INM combines organic and inorganic fertilizers to achieve balanced soil nutrition. Instead of relying solely on synthetic products, farmers blend them with compost or green manures. This approach reduces environmental impact, improves soil structure, and maintains long-term fertility.

Reducing Chemical Fertilizer Dependency

Overuse of chemical fertilizers can degrade soil over time. Transitioning to organic inputs or slow-release formulations ensures steady nutrient availability and reduces the risk of runoff. Adopting precision farming tools can also help monitor and optimize fertilizer application.

Promoting Biodiversity in the Soil Ecosystem

A diverse soil ecosystem supports better nutrient cycling. Earthworms, arthropods, and beneficial microbes each play unique roles in decomposition and mineralization. Encouraging biodiversity through reduced tillage, mulching, and organic matter addition enhances soil health naturally.

Real-World Examples of Successful Nutrient Cycle Management

Case Study: Regenerative Agriculture Techniques

Regenerative farmers worldwide are proving that healthy soils can be restored through mindful management. By combining composting, no-till methods, and rotational grazing, they enhance soil carbon content and microbial activity. The result is a self-renewing system that requires fewer external inputs and produces nutrient-dense crops.

Urban Gardening and Compost-Based Fertility Systems

Even in small spaces, urban gardeners are finding ways to close the nutrient loop. Community composting programs transform kitchen scraps into valuable soil amendments, reducing waste and improving plant productivity. Rooftop and container gardens using compost-based soil mixes demonstrate that sustainable nutrient cycling isn’t limited to rural farms.

Promoting Biodiversity in the Soil Ecosystem

A diverse soil ecosystem supports better nutrient cycling. Earthworms, arthropods, and beneficial microbes each play unique roles in decomposition and mineralization. Encouraging biodiversity through reduced tillage, mulching, and organic matter addition enhances soil health naturally.